09/30/2016. Remarks by

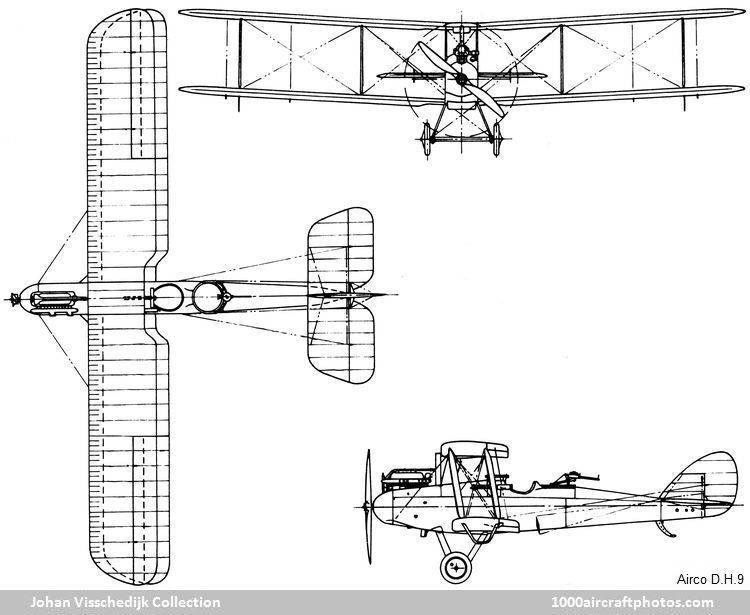

Johan Visschedijk: "The sudden demand for expansion of the bomber force following an unexpected daylight attack on Britain by German bombers on July 13, 1917 had to be answered urgently. The most rapid response was an extensively modified D.H.4 (serial A7559) that first flew the same month, July 1917. It had a top speed of 112 mph (180 kmh) and an extended range to reach further into enemy territory. To make use of existing tooling and minimize delays in getting the new type into service, the D.H.4 wings and tail were attached to a new fuselage with the pilot and observer/gunner in adjoining cockpits to improve communications. This new aircraft was the D.H.9 and it was substituted in all outstanding D.H.4 contracts.

The other major change was the power plant, the new 300 hp Siddeley Puma engine. However, this choice of the engine proved to be a mistake due to major production difficulties. Although these difficulties were eventually cleared up, the power was reduced to 230 hp and there was no suitable substitute engine available. This was reflected in poorer performance which made the aircraft more vulnerable to attack from enemy fighters, so operational range was limited to the endurance of the escorting scouts, while planned attacks were reduced in effect by aircraft dropping out due to defective engines.

The D.H.9 altitude was also limited in practice to around 13,000 ft (3,960 m) and the advantage of having the crew closer together was lost by the lack of performance. Eventually an alternative engine was tried, the Fiat A-12, tested on the second Airco production D.H.9 (serial C6052). The power was only a minor increase at 260 hp and the rate of production was so slow that it was too late to be of any use.

The internal bomb bay was another change, capable of holding two 230 lb (104 kg) or four 112 lb (51 kg) bombs, but the service trials only released the aircraft as suitable for day bombing because the pilot's vision was restricted by the lower wing. The D.H.9 was also fitted with a forward-firing synchronized Vickers machine gun and one or two Scarff-mounted Lewis guns in rear cockpit. Two fuel tanks were fitted behind the engine with a total of 84 gal (318 l).

D.H.9 (C6051) (

Van Swindelle Collection)

Deliveries began to build up at the end of 1917, the first production aircraft built by Airco (C6051 pictured above and on top of page) was delivered to the AES (Aeroplane Exprimental Station) Martlesham Heath on November 6, 1917. Three days later it was transferred to AES Orfordness, while on November 28 it returned to AES Martlesham Heath for further testing. By February 28, 1918 the aircraft was at 2 ASD (Aircraft Supply Depot) at Fienvillers, France, while parked there an aircraft of 25 Squadron crashed into it on March 25, 1918. Transferred to 1 ASD at Saint-Omer, C6051 was struck off charge on April 2, 1918 as damaged beyond economical repair."

No. 103 Squadron was the first unit to commence re-equipment with D.H.9s at Old Sarum in December 1917. It moved to France in May 1918, joining a number of other squadrons which were also equipped with D.H.9s, forming the VIII Brigade, of the Independent Force of the RAF. Losses were high, both due to enemy action and technical problems, and although they were no longer regarded as frontline combat aircraft by June 1918, production continued to replace the superior D.H.4s.

The combat attrition is shown by a raid flown on July 31, 1918, when twelve D.H.9s of No. 99 Squadron set out to attack Mainz, Germany. Three soon had to return with engine trouble and one was shot down. Over Saarbrücken another three were shot down by a large force of defending scouts. Whilst the five survivors dropped their bombs on the railway station, one of them crashed on the town. Two more D.H.9s were shot down on the way home, leaving only the CO, Captain Taylor and one other crew to return to Azelot, near Nancy, France. The enemy had also suffered casualties, but the squadron was unable to continue operations until replacement crews were available.

With plentiful stocks of D.H.9s, they were used more effectively in the Middle East and the Mediterranean area, where they did not have to contend with defending aircraft. Some were flown on reconnaissance duties, while others were used in their intended role of bombing. Other D.H.9s were allocated to Home Defence and coastal patrols replacing some of the D.H.6s, but no successes were claimed.

D.H.9 with Napier Lion engine (C6078) (

Gary Smith Collection)

In mid-1917, Arthur John Rowledge at the D. Napier & Son Ltd. at Acton, London, UK, started the design of a liquid-cooled twelve-cylinder engine with cylinders arranged in three groups of four, which were disposed in the form of a broad arrow (also known as a W-engine). Initially this engine was known as the Napier Triple-Four, and by September 1917 the manufacturers envisaged an output of 300 bhp at 10,000 ft (3,048 m). The engine was renamed Lion and one of the prototypes was experimentally fitted to a D.H.9 (serial C6078) and first flown at Farnborough on February 16, 1918, showing a number of teething problems.

By the summer of 1918 these problems, including the heating of the induction system, had been solved by the manufacturer and in September the first production Lion engine was fitted to the D.H.9 C6078, which had its airframe strengthened and had its retractable radiator increased in size. The aircraft was delivered to Martlesham Heath for service trials on October 20. Although it came too late for active service, the Lion engine proved ideal. Flown by Captain Andrew Lang and Observer Lieutenant Blowes, C6078 established a new altitude record on January 2, 1919, climbing to 30,500 ft (9,296 m) in 66 min 15 sec."

The United States planned to power their 14,000 D.H.9s on order with the Liberty 12A engine, but all contracts were cancelled with the Armistice, and only the RAF D.H.9s continued in limited service in the Middle East. Further surplus batches were supplied to Belgium, Holland, Canada, South Africa, New Zealand and Australia, where they remained in service until 1925.

By the end of the production in late 1918, a total of 3,204 D.H.9s were built by no less than fourteen companies:

D.H.9J (G-EBTN) (

Johan Visschedijk Collection)

On 1 March 1923, de Havilland was awarded a contract for the training of RAF reservists. Seven Puma-engined D.H.9s were used for this task and their life extended in 1926 when they were converted to de Havilland D.H.9Js with the installation of the Jaguar III radial engine, continuing in service until 1933. In all, fourteen D.H.9Js were registered between July 8, 1926 and October 14, 1931, the last were scrapped in 1936.

A small number of D.H.9s were converted for racing as single-seaters, and three competed in the 1922 King's Cup Air Race gaining third, fourth and tenth places. In 1923, Alan Cobham flew a Lion-powered D.H.9 to second place in the King's Cup at an average speed of 144.7 mph (232.9 kmh). Similar to the D.H.4RA, a civil racing conversion of the D.H.9A was the

D.H.9R with a Lion engine."